Or, why smart people fall for stupid cons

Hello, Simple Dollar and Weakonomics readers! I’m really glad you’re here. Enjoy your look around and take a look at my most recent post on buy-and-hold investing after you’re through reading this one. Remember to subscribe if you like what you see!

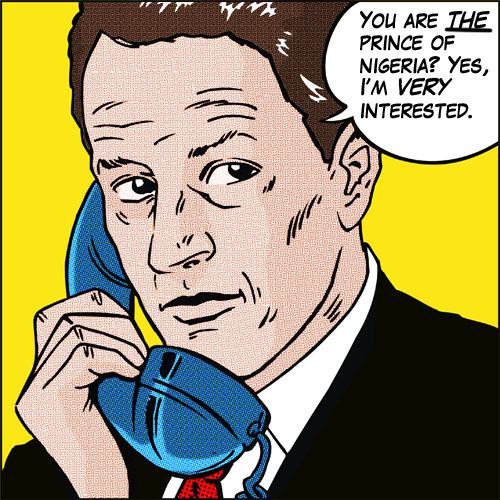

Sometimes, it mystifies me that so many people can fall for the oldest tricks in the book. Bernie Madoff’s operation was nothing more than a Ponzi scheme—you know, that scam that was invented in the 1920s. Do people really think that a random Nigerian prince selected them to handle gigantic sums of money? Does it really never occur to a tourist that a street-side card game probably isn’t on the up and up?

It mystifies me, that is, until I fall for one. Then the excuses get rolled out. Even in hindsight, you try to convince yourself that you’re not a sucker. There was no way you could have seen that coming.

So why is it that we fall for these silly cons? Researchers at the University of Cambridge decided to figure it out and boiled down their findings to seven principles that make us more prone to being tricked. I am simmering those down to four, because I found them the most interesting. But check out the whole study if you’re curious. Here they are, with direct quotations in italics:

1. The distraction principle

While you are distracted by what retains your interest, hustlers can do anything to you and you won’t notice.

Here’s what I want to know: In the Wizard of Oz, what took Dorothy and her friends so long to notice the man behind the curtain? I bet the giant, green, booming head had something to do with it. If you think about it, the man was really nothing more than a high-tech magician. Set up a big distraction, and you’ll keep their eyes away from where the real magic happens.

In the scammer world, this takes many forms. The street performer holds your attention, while a pickpocket works behind the crowd. A thief runs off with a woman’s purse at the airport, and while you’re in pursuit, the woman takes your luggage. It’s often hard to distinguish between a real distraction and an illusory one. So my advice would be to assume that they’re all fake, especially if you’re a tourist.

In the legal-but-shouldn’t-be world, you’ll get annuities salesmen trying to focus your attention on guaranteed returns, instead of high, back-end fees and surrender charges. Or maybe you’ll get a car salesman who lures you in with a low base price, but shows you the “delivery charge” after you’re already committed.

In one world, the perpetrator gets arrested, but let’s face it, it’s all the same.

2. The herd principle

Even suspicious marks will let their guard down when everyone next to them appears to share the same risks. Safety in numbers? Not if they’re all conspiring against you.

In the scammer world, the “herd” is the group winning money in the street-game you’ve stumbled upon. You think the game must be honest, because these guys win, right? Of course, it turns out that they’re all in on the con.

It wasn’t the study’s authors’ intention, but it’s oh-so-tempting to turn this into an investing lesson too. As a species, we get a lot of comfort in knowing that there are others succeeding or failing with us. Even if you think tech stocks are overpriced, if your neighbors are all making a killing in the sector, you’re tempted to buy in. Yes, you’re also jealous of their success, but if you fail, they fail. That feels good. It feels safe.

Of course, the scammers take it a step further. Not only are the playing off that safety-in-numbers, prehistoric mentality, they’re not actually sharing the risks.

3. The deception principle

Things and people are not what they seem. Hustlers know how to manipulate you to make you believe that they are.

One of my favorite scenes in Casino Royale is when a tourist in a hurry throws James Bond his car keys, thinking he’s the valet. I’ve got to admit, I don’t think I’ve ever questioned whether the man in uniform in front of the hotel worked there. Even if I did question it, I’d probably be too embarrassed to ask.

The BBC apparently tested a scam where they set up a fake ATM machine to see if pedestrians would be fooled and use their cards there. Of course, if they were real fraudsters, they’d get all of the customers’ debit card info and PINs. The operation worked better than they hoped for. You see, before they had even finished building the machine—that is, even while the machine’s back was exposed to the air—people kept walking up and trying to use it! Talk about “blinded by familiarity.”

Ever see an ad proclaiming “8% yield! Better than a CD!” in big letters and “Not FDIC-insured” in small letters? The bringer of this great investment opportunity is lowering your guard with a comparison to something you’re familiar with.

4. The need and greed principle

Your needs and desires make you vulnerable. Once hustlers know what you really want, they can easily manipulate you.

Ooh, it’s tempting to turn this one into an investing principle too. But staying on point: Find out what your mark wants more than anything, and then offer it to him. If your target is bankrupt, offer him money. If your target is lonely, offer him companionship. Afraid? Offer safety.

I could go on and on. But people do stupid things when they need something desperately. And that’s why even though we all roll our eyes when we hear about someone falling for the Nigerian Prince scam, none of us are safe from it—not if we were put into the right predicament.

Not all cons are illegal.

I hope you find ways to apply these principles in everyday life. People are trying to sell you all the time, and even though it’s not classified as fraud, oftentimes the sell works off these tenets. Everyone’s running a con. And knowing yourself goes a long way to stopping it.

Ed’s Note: Ok, an admission here. Astute readers will notice that this image has been used twice. No, I don’t plan to do that with regularity. I took down the first post with which the image ran—a rant on free credit report commercials—because it was, well, a rant. I looked at it a few days later and decided that’s not what this blog is about. So bear with me as I grow into the blog. Thanks for reading.

{ 6 comments… read them below or add one }

Robert Shiller says in his book Irrational Exuberance that the entire U.S. stock market is a “Ponzi scheme” at times of insane overvaluation (like what we saw from January 1996 through September 2008). I’ve pointed this out to people on numerous occasions. The two most common reactions I get are: (1) blank looks; and (2) open hostility.

I remember a comment that I saw on a discussion board when the stuff about Madoff was first coming out. A fellow said: “Oh, no! Madoff’s fund is not a Ponzi scheme. I made lots of money investing with him.”

People think that, if they made lots of money, it’s not a Ponzi scheme. But most successful Ponzi schemes make lots of money for at least some people (that’s how you win the confidence of the others). What makes something a Ponzi scheme is that the overvall promise cannot be met.

Rob

I’m not advocating this at all. But imagine how quickly over or undervaluation problems would disappear if companies paid 70% or 80% of their earnings out as dividends. Suddenly, a lot of novice investors would start to think of themselves as company owners. And they’d see earnings growth and buying companies at good prices as the key to making money in the market. Right now, you’re right that it feels like the easiest way to make money is to find the next sucker who will pay even more for a share.

Just a note on my iPhone, the zero tweets thing made it look like you had zero comments, because I couldn’t read the word.

Might want to change that. Nice blog though.

Loved the post…my first time here, and I love the artwork almost as much. Keep it coming!

Pop, you are right about dividends, but somehow Wall Street convinced the public, profits were better off in the hands of overpaid CEOs and top executives. Now they reap the rewards as if they owned the company, while investors take all the risk.

In theory the idea about dividends makes sense, but this ignores the reality of why the markets were created.

There is all kinds of talk about how companies want to create value for their shareholders. But this is not the primary goal of the markets. The markets were created so companies could have access to cheap capital. Unsophisticated inventors are the best source of cheap capital.

This is why institutional banks run retail brokerage operations – lines of business that lose money. The retail arms of the financial houses create a source of cheap capital for their institutional clients. They make the big bucks by charging fees to float securities for their institutional clients and by making a market in the securities.

At least this is how it was done in the past. Now they make money by borrowing from the Fed at essentially zero percent and turn around and make 4% by clipping coupons – no muss, no fuss.

Except for the wage earner, whose wealth is evaporated away by the inflation caused by the increase in the money supply that is necessary to lend out the money at zero percent.

Ain’t banking wonderful!

{ 2 trackbacks }