Plane crashes are not that common. And yet…

You’ve probably heard the old yarn about how we often overestimate the chances of dying in a plane crash. When I made a guess before beginning this post, I was actually off by a factor of ten. I, somewhat flippantly, guessed one in a million, when really the chances are closer to one in 11 million.

The mistake (too conveniently) illustrates the point of this post. Humans are notoriously bad at knowing how risky things are, which leads to all sorts of bad decisions we make with our money.

First, it’s important to talk about, um, why this is important. You see, most of the time when we talk about risk, we distinguish people by whether or not they have “risky” or “safe” attitudes. So, men, for example, tend to be more cavalier than women with putting a large amount into stocks, with the idea that they’re more willing to gamble for a big gain.

But a failure in risk perception breaks that model. It could be that men just don’t properly comprehend the risks associated with undertaking an endeavor. So, for example, a man could simply not know the risks in investing a certain allocation in stocks, rather than be more tolerant of them.

But before we get into that, let’s see how good you are at ranking certain non-financial risks.

What scares you the most?

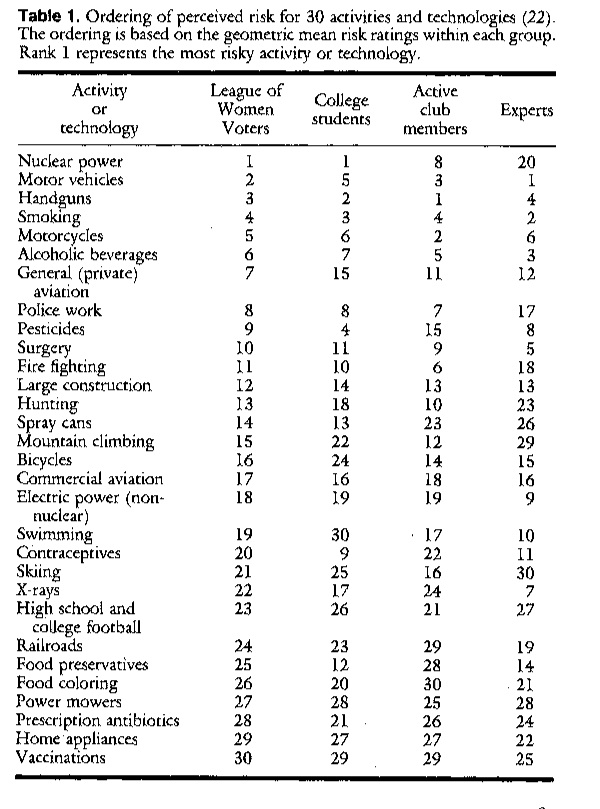

A couple decades ago, Paul Slovic, founder of Decision Research, and a couple other academics asked a few groups of people in Oregon to rank the “present risk of death” of 30 activities. The researchers then asked risk assessment experts to guess the risk. Later, the researchers found that experts’ guesses were extremely close to actual fatality risk, so we’ll just use them as a proxy for the truth.

Anyway, here’s how the ranking of perceived and actual risk ended up:

As you can see from the chart, with some kinds of events, the laypeople were spot on. Car accidents, indeed, are a leading cause of death, and the League of Women voters, college students, and the Active Club all accurately put that at least in the top five of death risk.

But some predictions on risk, were laughably off. Most notably, the League, students, and club all put “nuclear power” at least within the top 10 of death risk, when the risk was actually very low. You’d probably not put nuclear power very high up on the list yourself, but these surveys were conducted in the late 1970s, back when nuclear power was more closely associated with mushroom clouds than green energy. Though I think it’s worth noting, that the surveys would have been pre-Chernobyl.

The worst part: We’re really confident about perceived risk.

What are more common, homicides or suicides? Now, what odds would you put on your being correct?

A few researchers did this a couple years ago and found a large percentage thought homicides happened more frequently than suicides, apparently based on homicides’ prevalence in newspapers. Suicides happen much more frequently.

But more interesting, when asked to place odds on how sure they were in their answer, more than 30% gave their guess odds of 50 to 1 or greater. In other words, not only were they wrong, they were really sure in their wrong answer.

It doesn’t help when you’re an expert. Researchers asked seven, internationally known geotechnical engineers to set upper and lower bounds for at what height a clay embankment would collapse. They were supposed to be 50% certain that the actual height would be in the range. None of them picked a range that included the actual fail point. (Again, via Slovic.)

So not only are we bad at calculating risks, we’re really confident in ourselves despite that. Hopefully, if the test subjects were asked to put money on the bet, they’d be a little less cavalier. But in determining our stock allocation, we’re basically asked to estimate and wager on risks all the time.

The difference between improbable and impossible

The most common mistake I see in personal finance is confusing unlikely with impossible. It’s unlikely that stocks will fall or rise by an extreme amount on any given day, but it does happen. Consider this passage from a Forbes article last year:

A prime example: Oct. 19, 1987, when the S&P 500 fell 20% in a single day. The average move up or down over the past half century is 0.65%. By that measure, Black Monday was what is referred to as a 25-sigma event, meaning it was 25 standard deviations away from the mean. If you were to plot a normal statistical distribution, a 25-sigma event would happen … well … never. It would be less likely than winning the Powerball a trillion times a day every day for a trillion trillion trillion lifetimes.

Even ignoring Black Monday, if returns were “normal,” statisticians would expect the S&P 500 to move up or down by 3.5% or more only once every 10,000 years.

So, given what’s “likely” in any given time period, you’re likely to never see the S&P 500 move up or down by 3.5% or more in your lifetime. In actuality, that’s happened more than 100 times in the last 60 years.

And even though your chances of a loss in stocks gets smaller the longer you hold them, the possible loss gets greater. As said by Boston University professor Zvi Bodie (whom I embarrassingly mischaracterized earlier this year): “For example, say you have $500,000 and are three years away from retirement. If you suffer three years of 15% losses, your savings will be almost cut in half — and your retirement will be jeopardized. Of course, the longer the string of losses continues, the larger the shortfall will be.”

You can debate whether returns are related to each other in that way (i.e. does the chance of stocks dropping 15% go lower if they dropped 15% the previous year?), but all it takes is a year like 2009 or 2002 to recognize that extreme stock market events, while unlikely, can have dramatic impacts on your savings.

Another risk we’re probably not planning enough for: longevity risk. How many times have you put your “expected death” at 85-years-old in a retirement calculator? According to the Social Security actuarial tables, if a man is aged 85, he’s likely to live another 5 years if he’s already made it that far. (That’s not the same as a life expectancy at birth, which the SSA pegs at 75.)

Or how about our propensity to buy life insurance, but not to buy disability insurance? You’re probably more afraid of dying than of getting an injury or disease that prevents you from working, but according to the Health Insurance Association of America (admittedly an angle here…), about a third of us will get some sort of illness between the ages of 35 and 65 that prevents us from working for more than 90 days.

To make a long story short, don’t give short shrift to catastrophic unlikelihoods. And next time you’re sure of your chances on a bet, for God’s sakes, look it up.

This post was featured in the Carnival of Personal Finance at Simply Forties. Check it out!

{ 189 comments… read them below or add one }

← Previous Comments

I am not real wonderful with English but I come up this really easy to interpret.

Lift detox black

I really appreciate this post. I have been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You have made my day! Thank you again

Purdentix reviews

PRIME BIOME REVIEWS

Purdentix review

I appreciate, cause I found just what I was looking for. You’ve ended my 4 day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a nice day. Bye

Great site For Glass “Toys”

Hi my family member! I wish to say that this post is awesome, nice written and include almost all significant infos. I¦d like to see extra posts like this .

Bookmarking this for future reference, but also because The advice is as invaluable as The attention.

TONIC GREENS REVIEW

Great wordpress blog here.. It’s hard to find quality writing like yours these days. I really appreciate people like you! take care

Fantastic web site. Plenty of useful information here. I?m sending it to some friends ans also sharing in delicious. And certainly, thanks for your effort!

Throughout this grand scheme of things you actually get an A+ with regard to effort and hard work. Where you lost me personally was in your particulars. As as the maxim goes, details make or break the argument.. And it couldn’t be more accurate at this point. Having said that, let me inform you what exactly did deliver the results. Your authoring is highly convincing and this is possibly the reason why I am taking the effort to comment. I do not make it a regular habit of doing that. Next, despite the fact that I can easily see a leaps in logic you come up with, I am not necessarily certain of just how you seem to connect your details which in turn produce your conclusion. For right now I will subscribe to your issue however hope in the foreseeable future you link your facts better.

Hi there! Someone in my Myspace group shared this site with us so I came to look it over. I’m definitely enjoying the information. I’m bookmarking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Superb blog and great style and design.

I?m not certain the place you’re getting your info, but great topic. I needs to spend a while learning more or figuring out more. Thanks for magnificent info I used to be looking for this information for my mission.

What an informative and meticulously-researched article! The author’s thoroughness and aptitude to present complex ideas in a understandable manner is truly commendable. I’m extremely enthralled by the depth of knowledge showcased in this piece. Thank you, author, for providing your expertise with us. This article has been a real game-changer!

Thanks for the good writeup. It in truth used to be a amusement account it. Glance advanced to more delivered agreeable from you! By the way, how can we be in contact?

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it’s truly informative. I am gonna watch out for brussels. I will be grateful if you continue this in future. A lot of people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

http://www.arttree.com.au is Australia Popular Online Art Store. We sell Canvas Prints & Handmade Canvas Oil Paintings. We Offer Up-to 70 Percent OFF Discount and FREE Delivery Australia, Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, Hobart and all regional areas.

I have recently started a site, the info you offer on this website has helped me greatly. Thank you for all of your time & work.

This is without a doubt one of the greatest articles I’ve read on this topic! The author’s extensive knowledge and zeal for the subject shine through in every paragraph. I’m so thankful for coming across this piece as it has enriched my knowledge and ignited my curiosity even further. Thank you, author, for investing the time to produce such a phenomenal article!

An fascinating dialogue is price comment. I feel that you need to write extra on this subject, it won’t be a taboo topic but generally people are not sufficient to talk on such topics. To the next. Cheers

Wow! This can be one particular of the most helpful blogs We’ve ever arrive across on this subject. Actually Wonderful. I am also a specialist in this topic so I can understand your hard work.

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it’s really informative. I am going to watch out for brussels. I will be grateful if you continue this in future. Numerous people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

A few things i have seen in terms of laptop or computer memory is always that there are specs such as SDRAM, DDR or anything else, that must go with the technical specs of the mother board. If the pc’s motherboard is rather current while there are no operating-system issues, changing the memory space literally requires under 1 hour. It’s among the easiest computer system upgrade techniques one can visualize. Thanks for spreading your ideas.

I?ve read some excellent stuff here. Definitely worth bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how so much effort you place to create any such fantastic informative site.

Oh my goodness! an amazing article dude. Thanks However I am experiencing challenge with ur rss . Don?t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anybody getting identical rss problem? Anyone who knows kindly respond. Thnkx

I have come across that right now, more and more people will be attracted to digital cameras and the field of taking pictures. However, like a photographer, you must first expend so much period deciding which model of photographic camera to buy along with moving out of store to store just so you might buy the least expensive camera of the brand you have decided to pick. But it doesn’t end now there. You also have take into consideration whether you should buy a digital digital camera extended warranty. Thanks a lot for the good recommendations I gathered from your blog site.

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article author for your weblog. You have some really great articles and I believe I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d absolutely love to write some material for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please shoot me an email if interested. Cheers!

Hey there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words in your article seem to be running off the screen in Safari. I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to do with web browser compatibility but I figured I’d post to let you know. The style and design look great though! Hope you get the problem fixed soon. Kudos

Thank you for another informative website. Where else may I am getting that type of information written in such a perfect approach? I have a challenge that I am just now running on, and I’ve been at the look out for such info.

Thanks for the points you have provided here. Another thing I would like to convey is that personal computer memory needs generally rise along with other advances in the engineering. For instance, any time new generations of processor chips are introduced to the market, there is usually a matching increase in the dimensions calls for of both computer system memory and hard drive space. This is because the program operated by way of these cpus will inevitably boost in power to use the new technologies.

By my observation, shopping for electronic products online can for sure be expensive, however there are some principles that you can use to obtain the best products. There are continually ways to obtain discount offers that could make one to hold the best electronic devices products at the smallest prices. Thanks for your blog post.

Just wish to say your article is as surprising. The clearness for your put up is just great and i could think you’re knowledgeable on this subject. Fine together with your permission let me to clutch your RSS feed to keep up to date with drawing close post. Thanks 1,000,000 and please keep up the enjoyable work.

http://www.mybudgetart.com.au is Australia’s Trusted Online Wall Art Canvas Prints Store. We are selling art online since 2008. We offer 1000+ artwork designs, up-to 50 OFF store-wide, Budget Pricing Wall Prints starts from $70, FREE Delivery Australia & New Zealand and World-wide shipping. Order Online your canvas prints today at mybudgetart.com.au

http://www.mybudgetart.com.au is Australia’s Trusted Online Wall Art Canvas Prints Store. We are selling art online since 2008. We offer 1000+ artwork designs, up-to 50 OFF store-wide, Budget Pricing Wall Prints starts from $70, FREE Delivery Australia & New Zealand and World-wide shipping. Order Online your canvas prints today at mybudgetart.com.au

When I initially commented I clicked the -Notify me when new feedback are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get 4 emails with the identical comment. Is there any method you may remove me from that service? Thanks!

Good article. It is very unfortunate that over the last several years, the travel industry has already been able to to handle terrorism, SARS, tsunamis, flu virus, swine flu, as well as the first ever true global economic collapse. Through it the industry has really proven to be powerful, resilient and also dynamic, discovering new solutions to deal with trouble. There are continually fresh problems and the possiblility to which the business must yet again adapt and react.

← Previous Comments

{ 1 trackback }