Hello Frugal Dad visitors! I’m flattered you stopped by. I’d be even more happy if you came by on your own! Here are a few reasons why you should:

1. This ain’t your typical personal finance blog. I don’t often tackle the basics of a Roth IRA or how to choose a money market account. I do write about the cutting edge of behavioral finance and how it should affect the choices you make.

2. I won’t overload your inbox or feed reader with posts. I only post two or three times a week, but I try to swing for the fences with every one. That might be part of the reason I’ve been an editor’s pick in five carnivals of personal finance, despite only being around for a couple months.

3. I have cool art. There’s more than one reason it’s called Pop Economics. So please subscribe!

Economists take on our long workweek, how it got this way, and what to do about it.

By now, our workweek should just be a few days. At least, that’s what economists predicted in 1958. Put another way, if we kept up the current 40- to 50-hour workweek, they predicted we’d have an average retirement age of 38.

As you know, that didn’t happen. I’ve been thinking about that stat a lot in the last couple weeks. Work has taken up a huge chunk of my time, which you might have noticed has resulted in a rather light posting schedule. Sorry about that. I’m going to start writing ahead over the weekend so my full-time job travails don’t interfere with your Pop enjoyment.

But seriously, you might wonder how it so happened that we’re working just as much now as we did in the 1940s. Until the 1950s, the workweek was consistently getting shorter. In 1791, carpenters in Philadelphia went on strike in a fight for a 12-hour, 6 am to 6 pm workday (minus two hours for meals). The 8-hour work day wasn’t a serious consideration for most workers until the late 1800s, and it didn’t become an American standard until the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938.

But economists thought it was only going to get better. You see, our per capita productivity was increasing at a rate of about 3% per year in the middle of the last century. As our productivity improved with technological innovations, we’d be able to create the same standard of living with less work. Eventually, we would only have to work a fraction of the week.

In fact, right now, we could reproduce the average standard of living Americans enjoyed in 1948 with half the amount of work it took to produce then. You could work four-hour days, or 2.5 days a week, or six months per year.

As you know, that didn’t happen. Instead, our work weeks actually got longer. Over the past few decades, we’ve added about 10 hours to the average work week.

Just two days ago, I was griping about how it seems like I only have time to eat and sleep before going back to the office. And my job’s relatively lax at about 45 hours per week. Lots of accountants, bankers, consultants, and lawyers spend 80+ hours tied to desks and BlackBerrys.

Instead, rather than buying more time as our productivity increased, we bought more stuff. We have comforts workers in the 1940s could only dream of. Unfortunately, we also have the same workweek.

Taking our time back

I read the bestselling 4-Hour Workweek a couple years ago. What made that book so seductive was the promise that you could limit your work hours but still experience the same or an even better standard of living that you have now. I’m not quite as optimistic. But the book’s a great primer on life re-engineering.

You see, we work eight-hour weeks because our employers tell us we have to. I’ve done the math—by cutting out my TV and internet service, moving to a less pretty but perfectly fine neighborhood, and limiting the travel I’ve gotten accustomed to, I could live on a little less than 3/4 of what I make now. That means I could live pretty comfortably by working 28 hours a week.

But in most cases, your boss won’t entertain an offer to work less for less pay. It’s just not built into our culture. Hard work is rewarded with more money, not more time. Just recently, I admired a co-worker who did make this kind of dream arrangement. When it was time for layoffs, she was the first to go.

How could this change? With more companies choosing to rebuild their staffs with freelancers (i.e. independent contractors) instead of full-blown employees, we might get to make this choice soon. As a freelancer, you decide how much you want to work (at least, you have more freedom than a regular employee). It comes at the expense of guaranteed work, paid time off, sick leave, cheap healthcare, and a host of other benefits. But it’s one little plus.

What can you do now?

I’m going to go out a limb here and guess that you’d rather not wait for America’s heavy work culture to change. Here are six ways to scale back on your work life and get some free time back, starting with the most extreme possibilities and ending with minor tweaks.

1. Move.

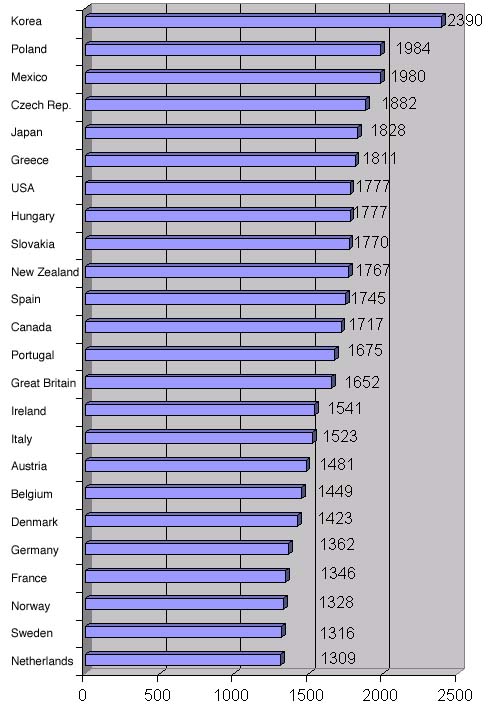

America’s workweek has been growing for some time. The workweeks of other countries continued to shorten with productivity increases. The average U.S. employee works 1,777 hours per year. But you can easily find other countries and cultures that value free time much more highly (See chart). Employees in the most carefree countries on this list work more than 20% fewer hours.

Another fascinating fact: The countries that consistently rank as having the world’s “happiest people” also tend to work fewer hours than people in the U.S.

Among the winners as measured by Gallup: the Netherlands (1,309 hours a year), Denmark (1,423), and Canada (1,717). Apparently people in those countries aren’t missing whatever money or items they’re giving up by working less.

2. Work for yourself.

And by this, I don’t mean start your own business that you may or may not grow into a multimillion-dollar empire. This is about working less, not making more.

Freelancers effectively get to decide how much they need or want to work and can scale back whenever they want to take time off. Sure, you’ll be at an employer’s beck and call from time to time, but they don’t have the same amount of control over you as if you worked for them full time.

Switching to freelance can be rough and scary. That’s why so many people don’t become freelancers until they’re effectively forced to by a layoff. The hardest part will be building up a portfolio of clients. But if you choose to freelance within your previous industry, you’ll already have one potential client in the bag: your last employer.

Here’s a great article from Entrepreneur magazine on making the transition.

And one tip from me: You can use middlemen like Elance as you’re building up a portfolio or finding new clients, but these kinds of sites tend to bring a big concentration of little jobs that pay well below their required effort.

You’ll also be competing against workers in developing countries, who will push prices down below what you can afford. Your best clients are going to be the ones with whom you’ve developed a personal relationship and from whom you don’t need a middle man to protect you.

3. Discuss a work-from-home arrangement with your boss.

This will work best if you’re not a trailblazer in your company. As I mentioned before, one of the first people at my previous employer who did it got laid off last year.

But many companies have introduced formalized work-from-home arrangements for employees, in part to cut their own costs. They get to save on utility bills and office rent, and you get to eliminate your commute and the pressure of a boss watching over your shoulder.

Working from home also lets you measure a successful day by the amount of work you get done rather than the number of hours you spend in an office. That means you might be able to finish a project in half the time it took when coworkers stopped by to recap yesterday’s Real Housewives of New York City episode.

You can either leverage that to raise your productivity and pay or to shorten your workday by a bit. Of course, your boss might still want you to be on call for the workday. Just make the ground rules clear from the outset. This is a big theme in The 4-Hour Workweek.

4. At your next review, get a vacation raise.

Most corporate ladders are designed to reward employees with money instead of time. Assuming we only want money to use as a tool for happiness, this makes no sense.

Depending on what economic study you turn to, you’ll read that happiness increases with income only until you hit about $50,000 to $60,000 per year. Beyond that, each additional dollar of earnings doesn’t impact your level of happiness.

I don’t see how workers and companies haven’t caught on. Leaving the issues of kids, stay-at-home spouses, and expensive cities aside, we shouldn’t want to earn more money after we hit $60,000 or so a year. A dollar that doesn’t buy happiness, isn’t worth anything!

On the other hand, cash-strapped companies are more apt to grant you an extra few vacation days than a substantial raise. In fact, some companies would much rather give you that.

It’s not a bad strategy to ask your boss for a monetary raise first if you know he can’t give one and then back down to a few extra vacation days as an alternative. If you end up being too busy to take the days or depart the company without taking them, it’s many companies’ policies to pay you their monetary equivalent in cash. So there’s not much pain in getting a vacation raise.

5. Take advantage of benefits your company has already built in.

One company I worked for granted its employees a one-year paid sabbatical for every 10 years of work they put in. I knew plenty of people who had worked there for decades. I knew no one who took them up on it.

There seemed to be two fears held by the eligible employees: 1. That the company would realize it didn’t need them and would fire them if layoffs were needed. And 2. That they’d fall behind their peers on the promotion ladder.

Number 1 was a little delusional—if you’re unessential to a company, your boss is probably smart enough to know that without you disappearing for a year.

Number 2 was probably true. If Bill takes a year off and Nancy doesn’t, Nancy’s probably going to make vice president at least a year sooner. But I think most employees underestimated the benefits they got with a whole year off. They could spend more time with their children, go on life changing trips, get a new degree or certification, or explore a new career path. Are those things worth postponing a promotion? Heck yeah.

Few companies have a generous policy like that (academia excepted), but most do have special circumstances that let you take extended leave. After the birth of a child, some companies let both women and men take a few months off to take care of the newborn. If you have a sick parent, federal law will guarantee your job for up to three months while you take care of him. When you get the chance for a breather, take it.

6. Shorten your commute.

One of my cousins once told me, “The secret to happiness is a short commute.” And it turns out there’s data to back it up. According to Swiss economists Bruno Frey and Alois Stutzer, a worker with a one-hour commute has to earn 40% more money to be as happy as someone who walks to work.

They concluded that part of it has to do with the unpredictability of traffic—we never get accustomed to a long drive because traffic varies from fine to extremely bad. So think twice before buying a huge home in the suburbs.

Well, that’s what I’ve got. If you’ve got any other ideas or little tweaks you use to spend less time in the office, leave them in the comments. I’m looking for ideas!

P.S. This post appears in the Carnival of Personal Finance at The Wisdom Journal. Check it out for posts by other bloggers.

{ 7 comments… read them below or add one }

It’s also possible that in the U.S., much of our identity is tied up in work. This is a big country and people move from region to region all the time. So unlike other countries where most people might have much more connections to friends and family once they leave work, Americans only have their immediate family and neighborly acquaintances at home. As much as you might love your family, the daily routine might give working for money/material possessions an extra weight in the choice.

Sounds like the first step in reclaiming work hours is deciding whether you should in the first place. A vacation where you just sit around at home and deal with ordinary life might send you back to work in a flash.

Genius article. I totally agree, on all points. You’re absolutely bang on.

The economists begin with an assumption that employers only pay us when we contribute something to the bottom line. My experience is that that is often not the case. Many workers are being paid for political reasons. Perhaps the boss is paid according to how many workers work under him, so he needs to build his empire up to a certain size. Many of the people who comment at discussion boards and blogs are workers bored because they have nothing else to do; posting drops dramatically on weekends, when people supposedly have more free time.

So we’re really just killing time. We could do the real work that must be done in much less time and then be free from work. As a culture, though, we are not comfortable with that today. So we have devised ways to fill up the hours in which we no longer need to work to generate the productivity needed to cover the costs of living.

I think we need a new economics to push things to the next stage.

Rob

This is already happening. There are many school systems that operate on 4 day work weeks. The Peach County school system in Georgia went to a 4 day week this year. Eight school districts in one area of Colorado have adopted it, and the Klamath County system in Oregon is considering it for next year. It is saving school systems millions of dollars. Given the continuing declines in tax revenues, this trend is likely to continue to grow.

I know several people in the corporate world who job share. Each works a 20 hour week – one works the first 20 hours of the week, and the other works the last 20 hours. They use the same desk and together they make up one full time employee.

I know others, both men and women, who have negotiated to end their workday a couple of hours early so they can be home at the same time their children get home from school. Some took a prorated pay cut, some were able to negotiate keeping the same salary. These are special arrangements made between employee and boss, outside of official company HR policy. Some of these arrangements date back to the late 1980s. I have even heard of people asking for and getting a demotion – a different job at lower pay with fewer hours.

I think those who work hard do so because they choose to. Working long hours is a choice. For many, it may not be a mindful choice. For those who make the mindful choice to work less, I think making it happen goes back to what a wise man once said – you do not have because you do not ask.

I think if more of us asked for these kinds of things, we would get it.

I live in one of the countries at the bottom end of your graph (Sweden) and although the avarage work hours per year are lower here there are a lot of us in qualified jobs that work too many hours. My strategy is a version of point 5 above. I take maximum advantage of the possiblilites to work less (e.g. parental leave, vacation, work time reduction) and if I still can not get my work time down to the 20-30 hour work week I am looking for on avarage I save the money I earn from working more and that money can be used later to work less (e.g. a year of from work, extended vacations, early retirement etc.)

Nicely done. So impressed, I’m going to subscribe. Interesting on the first item with the amount of time other countries work per year. I read the list and immediately thought, “aren’t the happiest countries in the world at the bottom? I wonder if there’s a correlation?” Then, I read your next two paragraphs. I’m going with great minds think alike.

Ok, first I have to admit that I came from Frugal Dad. Hey, but at least I came, right? Excellent article! And very insightful. Thank you for the time and research you put into it.

Great information and amusing to boot: Number 1 was a little delusional—if you’re unessential to a company, your boss is probably smart enough to know that without you disappearing for a year.

{ 5 trackbacks }